Daniel Grizelj/DigitalVision via Getty Images

Over the past month, an unwind of the Japanese Yen (JPY:USD) carry trade contributed to major choppiness in global markets. The waters have calmed, but concerns about a Chinese Yuan (CNY:USD) unwind are already brewing. Could a reversal in the Yuan carry trade cause the next global financial tsunami?

Overview of JPY carry trade

To begin with, here is some background on what happened with the JPY carry trade.

In a typical carry trade, an investor borrows (goes short) in one currency at a low-interest rate and then invests (goes long) in another currency at a higher interest rate.

Often the long currency is invested into other assets like stocks or bonds. The trade is profitable when the gain on the long position is greater than the cost of holding (or carrying) the short position.

Low-interest rates in Japan have long made the JPY a popular source for carry. In 2013, Japan’s late Prime Minister Shinzo Abe introduced a series of aggressive economic policies (aka “Abenomics”) to fight anemic growth and deflation.

In addition to a zero-interest-rate policy (ZIRP), it included an unprecedented level of quantitative easing (QE) from the Bank of Japan, whereby the central bank purchased financial assets to ease interest rates further and increase market liquidity.

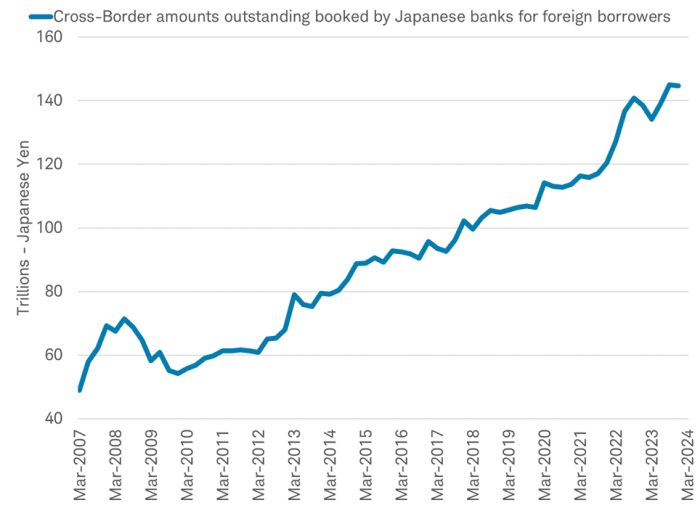

With money flowing free in Japan, the JPY carry trade ballooned. The exact amount is unknown, but data from the Bank of International Settlements shows foreign lending in Yen reached a massive one trillion USD in March 2024.

(Bank of International Settlements, Charles Schwab & Co)

In July, the Yen began a move up against the US Dollar ahead of an anticipated rate hike from the Bank of Japan (BOJ). On July 31st, the BOJ surprised markets by being more aggressive than expected with rate hikes and quantitative tightening (reversing QE).

The BOJ surprise and rising expectations of rate cuts in the U.S. led to a spike in the Yen and a vicious cycle of losses. As the Yen rose, carry traders saw losses on their JPY shorts and sold their long stocks to cover. That activity pushed JPY even higher and stock prices even lower. The result was losses on both sides of the carry and panic, which fueled the cycle further.

The JPY jumped +14% between July 10 to August 5. On August 5, the Nikkei Stock Average plummeted -12.4%, its worst day since Black Monday in 1987. The S&P 500 fell -3%, its worst day since 2022.

Fortunately, the panic was short-lived and markets rebounded during the week. However, before the market waters fully calmed, investors were already whispering about how an unwind of the Chinese Yuan carry could be the next big wave.

Will the Chinese Yuan unwind be different?

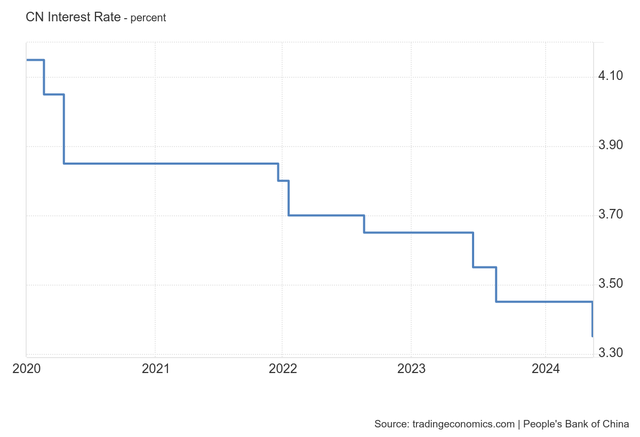

Like the rest of the world, China stimulated and cut interest rates following the COVID-19 pandemic. However, China’s tepid recovery caused the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) to keep monetary policy loose even while central banks like the U.S. Federal Reserve tightened.

(Trading Economics, Bank of China)

The divergence between rising U.S. rates and falling Chinese rates fueled a rising popularity in the Chinese Yuan carry trade. In the past month, the Chinese Yuan has moved upward against the USD, triggering concerns of another unorderly unwind.

Some fear the Yuan unwinding will be worse than what happened with JPY. This is understandable because China is the world’s second-largest economy and a leading global exporter. China has also been aggressively pushing for wider adoption of the Yuan with ambitions to make it a global reserve currency.

From that perspective, the unwinding of the Yuan trade sounds alarming. However, the Chinese Yuan and Japanese Yen have several important differences. Those differences may make an unwinding in Yuan less consequential than in Yen.

Different markets

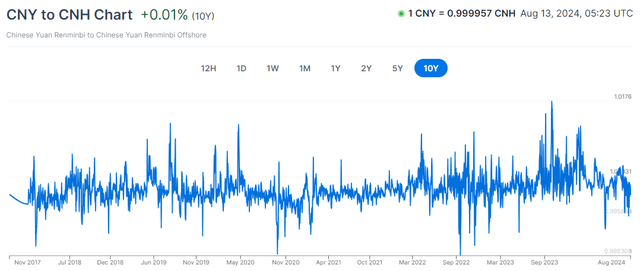

First, unlike the global market for the Japanese Yen, there are two distinct markets for the Chinese Yuan. An onshore (or domestic) market for CNY, and an offshore (or foreign) market for CNH. Despite the different markets and names, CNY and CNH represent the same underlying Chinese Yuan (aka RMB to be more confusing).

The onshore market is subject to direct government controls, including a managed price for CNY, while offshore CNH is not directly controlled and is more free-floating. Prices can diverge in the short run, but they converge over time and CNY tends to guide the price overall.

(xe.com)

That is because CNY is managed and also because the CNY market is much larger. According to the Bank of International Settlements, the average daily trading volume for onshore CNY is ~325 billion USD, versus ~125 billion for offshore CNH.

The point is the Chinese Yuan is ultimately a managed currency subject to direct controls by the government. This is very different from JPY, which is a free-floating currency driven by market forces. For that reason, CNY is unlikely to see the same extreme moves as JPY.

Different policies

Second, unlike Japan, China remains on a stimulative policy path. Challenges related to an ongoing real estate crisis, weak domestic spending, and a nascent recovery in manufacturing are more likely to invoke a rate cut than a hike from the PBOC.

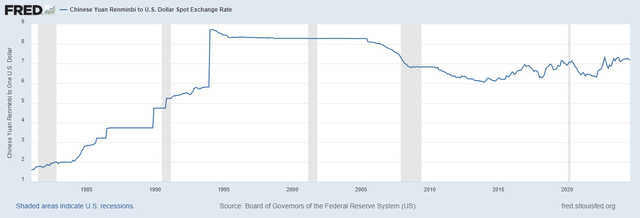

Regardless of economic conditions, the Chinese government has a long record of preferring a weak Yuan to promote its exports and account surpluses. China has adamantly kept the Yuan weak and within a narrow band of the USD for decades, to the point of being labeled a currency manipulator. It seems unlikely that China will change its behavior due to carry traders.

(Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis)

Different significance

Third, but not least, the Japanese Yen is still more widely used in global markets than the Chinese Yuan. According to the Bank of International Settlements, the average daily trading volume for JPY is ~1.2 trillion USD, multiple times higher than CNY and CNH combined.

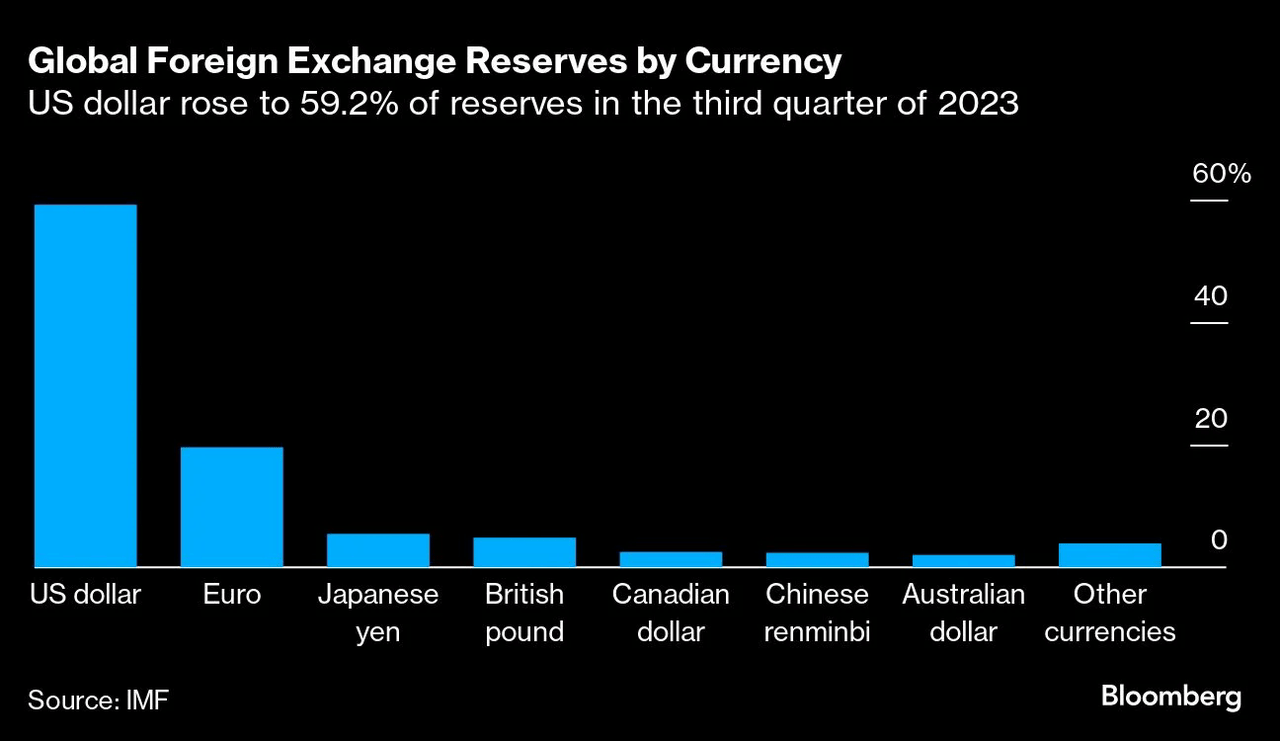

In addition, JPY is widely seen as a global reserve currency. According to the International Monetary Fund, the Japanese Yen is the third-largest foreign currency holding among central banks, the USD and the Euro are first and second, respectively.

(International Monetary Fund)

The choppy bottom line

An unwinding of the Chinese Yuan carry trade could, very well, make the next wave in financial markets. However, on its own, it may not be as devastating as an unwind of the Yen because CNY is a managed currency, China is most likely to keep the Yuan weak, and the Yuan is still less significant than the Japanese Yen globally.

To be clear, I am not making a prediction and I do not know what will happen. I am pointing out differences between the Yen and Yuan and extrapolating which unwind I believe would be worse, by itself, and irrespective of anything else.

I am also not dismissing the consequences of a Yuan unwind. The unwinding of any lopsided global trade has the potential to be devastating. Even if an unwind is orderly, unpredictable knock-on effects could escalate into a worse situation. In the late 1990s, Thailand’s currency devaluation morphed into a global market rout that did not end until the dot-com bubble burst in the U.S.

A global financial tsunami caused by the unwinding of an unremarkable carry trade looks unlikely, but certainly is still possible. Anything can happen, often when least expected. As investors, we are just boats bobbing on the market’s choppy waters. Though we cannot control the tide, we can stay alert at the wheel. We can also understand our exposures, manage our risks, and enjoy the ride.

Editor’s Note: This article covers one or more microcap stocks. Please be aware of the risks associated with these stocks.