The Global South-oriented organization BRICS has released plans to transform the international monetary and financial system and challenge the dominance of the US dollar.

As the chair of BRICS for 2024, Russia proposed the creation of a BRICS Cross-Border Payment Initiative (BCBPI), in which members of the organization will use their national currencies to trade.

BRICS will likewise establish an alternative messaging infrastructure to circumvent the SWIFT system, which is overseen by the United States and subject to Western unilateral sanctions.

This “multi-currency system” will also include new mechanisms not only to de-dollarize trade, but also to encourage investment in BRICS members and other emerging markets and developing economies, including a BRICS Clear platform, a “new system of securities accounting and settlement”, and financial instruments denominated in national currencies.

BRICS will experiment with distributed ledger technology (DLT, such as blockchain), promoting the use of central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) so nations can settle trade imbalances directly, without the need for correspondent banks located in third countries or the SWIFT interbank messaging system, which is dominated by the United States and subject to Western unilateral sanctions.

There are also plans for the establishment of a BRICS Grain Exchange and associated pricing agency, with centers for trade in commodities like grain, oil, natural gas, and gold, which can likewise be used to settle trade imbalances.

These proposals were outlined in the report “Improvement of the International Monetary and Financial System”, which was co-authored by the Ministry of Finance of the Russian Federation, the Bank of Russia, and the consulting firm Yakov and Partners. (A PDF of the document can be found at the official website of the Russian finance ministry, although if that link does not work, it is also available at the page of Yakov and Partners.)

This historic report was published on the eve of the BRICS summit in Kazan, Russia from October 22-24.

BRICS was originally founded as a loose grouping of emerging markets and developing economies, consisting of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa.

The organization has since expanded, and in the 2023 BRICS summit in Johannesburg, South Africa, six more countries were invited to join: Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Argentina. (Argentina’s left-leaning government had initially accepted the offer, but when right-wing pro-US leader Javier Milei came to power in December 2023, he attacked BRICS and refused to join.)

The chair of BRICS rotates on an annual basis. South Africa held the chairmanship in 2023, and was followed by Russia in 2024.

In February 2024, the finance ministers and central bank governors of BRICS met in Sao Paulo, Brazil. There, the Russian finance ministry and central bank said they would prepare a report “for BRICS countries’ leaders with a list of initiatives and recommendations on ways to improve the international monetary and financial system”.

Russia’s Finance Minister Anton Siluanov stated, “The current system is based on existing Western financial infrastructure and the use of reserve currencies. It is severely flawed and is increasingly used as a tool of political and economic pressure. Another reason for a reform of the international monetary and financial system is the geo-economic fragmentation that became a result of the abuse of trade and financial restrictions”.

In this February meeting, BRICS announced plans to create a “multilateral digital settlement and payment platform” it called BRICS Bridge, which “would help to bridge the gap between the financial markets of BRICS member countries and increase mutual trade”.

These efforts culminated in the comprehensive research released in October.

US-led West’s monopoly over international monetary and financial system

The Russian BRICS chairmanship report argued that international monetary and financial system (IMFS) is not only unjust but also inefficient, as it is a monopoly that suffers “from excessive reliance on a single currency and centralized financial infrastructure”.

The document noted that the “current IMFS is primarily serving interests of AEs” (advanced economies) – that is, largely the wealthy countries of the West.

Moreover, the “existing IMFS has been characterized by frequent crises, persistent trade and current account imbalances, elevated and rising public debt levels, and destabilizing volatility of capital flows and exchange rates”, it added.

The monopoly that the United States has exercised over the IMFS, ensuring global demand for dollars, has allowed Washington to weaponize its currency.

The US government is waging economic war around the world, having imposed unilateral sanctions on one-third of all countries, including 60% of low-income nations.

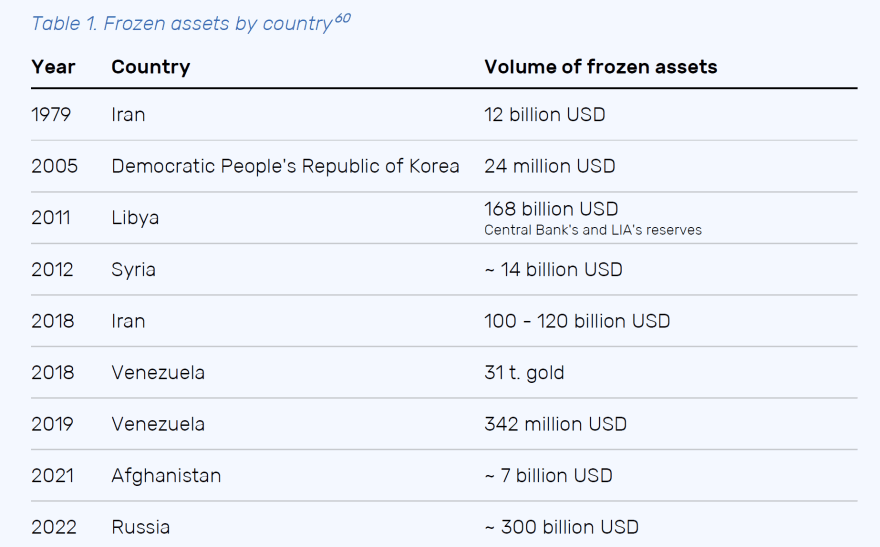

Washington and its allies in Europe have likewise seized hundreds of billions of dollars of assets from their adversaries. The BRICS report included a list of countries whose reserves have been frozen by the West, including Russia, Venezuela, Iran, Syria, Libya, Afghanistan, and the DPRK (North Korea).

BRICS alternatives to World Bank and IMF: New Development Bank (NDB) and Contingent Reserve Agreement (CRA)

To try to transform the international monetary and financial system, the Russian report proposed the creation of several new institutions, including the BRICS Cross-Border Payment Initiative (BCBPI), BRICS Clear platform, and BRICS Grain Exchange.

It also called to strengthen the organizations that BRICS has already created as alternatives to the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF): the New Development Bank (NDB, formerly known as the BRICS Bank) and the Contingent Reserve Agreement (CRA).

The NDB was created to provide financing for developing countries, especially for infrastructure projects. The NDB has pledged to offer more loans in the national currencies of BRICS members, not US dollars.

The Russian BRICS chairmanship called for “substantially increasing the NDB’s financing capacity, along with a simultaneous review of its principles and assessment criteria for the selection of projects with the aim of expanding the project pipeline”.

There is less optimism about the CRA. This institution was founded as an alternative source of liquidity for countries encountering balance of payments problems. It has not been very active, however, and the Russian proposal explains that the CRA suffers from two key challenges: its relies on the US dollar and it uses the SWIFT system.

Another serious concern with the CRA is that its operations are overseen by the IMF. The report noted that “the treaty establishing the CRA limits the amount of resources that can be released without a parallel arrangement with the IMF to 30% of the maximum”, and that any deals must company “with the IMF’s obligation on surveillance and disclosure”.

“This has the potential to result in a situation whereby a recipient, due to its current standing with IMF is deprived of a financial lifeline even if BRICS CRA members are in consensus regarding the provision of aid”, the document added.

The problem with the IMF and World Bank is that the bodies are thoroughly dominated by the Western powers. The United States is the only country that has veto power in both institutions.

When the IMF and World Bank were created at the Bretton Woods Conference in 1944, which also established the dollar as the global reserve currency, the Western powers were given significant control over the bodies. (At the time of the conference, much of the world was still formally colonized by the European empires.)

Every president of the World Bank has been a US citizen, and every managing director of the IMF has been European. There is an unspoken agreement that this pattern will continue.

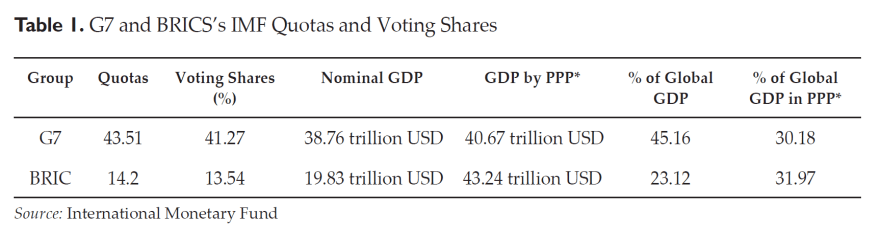

The original BRICS countries make up 32% of global GDP (measured at purchasing power parity, PPP), but have only 13.54% of voting shares in the IMF.

On the other hand, the G7 nations hold 41.27% of the voting shares in the IMF, despite the fact that they comprise just 30% of global GDP (PPP).

The BRICS report highlighted these problems, writing (emphasis added):

The governance aspect of the IMF has also been called into question – the system provides significant advantage to high-income economies, which hold key stakes in the IMF. The interests of 35 advanced economies are represented by 12 directors, while the remaining 155 countries are either represented by 12 directors from developing countries, or are included in constituencies with advanced economies, where their opinions and interests considered secondary. Directors from high-income countries have 63% of the votes at the IMF, although at purchasing power parity these economies now account for only 46% of global GDP.

Given these structural imbalances, the document called for the strengthening of the NDB and the significant reform of the CRA, so they can serve as true alternatives.

Will BRICS create a reserve currency to challenge the dollar? The SDR is a start

The Russian BRICS chairmanship report revealed that, in the short to the medium term, the bloc will try to de-dollarize by promoting trade and investment in national currencies.

There has been much debate, however, as to whether or not BRICS will ultimately create an international unit of account to challenge the US dollar’s role as the global reserve currency.

When the modern financial system was created at the Bretton Woods Conference in 1944, renowned economist John Maynard Keynes had proposed an international unit of account he called the Bancor.

As the IMF explains in its official glossary (emphasis added):

In his original proposal for a post-war international monetary system, British economist John Maynard Keynes envisaged a global bank (the International Clearing Union or ICU), which would issue its own currency (bancor), based on the value of 30 representative commodities including gold, exchangeable against national currencies at fixed rates. All trade accounts would be measured in bancor, while each country would maintain a bancor account vis-à-vis the ICU (expected to be balanced within a small margin), and also have an overdraft allowance vis-à-vis the ICU.

When countries experienced large trade deficits (more than half of the bancor overdraft allowance), they would pay interest on their accounts, undergo economic adjustments (possibly also capital controls) and devalue their currencies. Conversely, countries with large trade surpluses would also be subject to a similar charge and required to appreciate their exchange rates.

Keynes expected that this mechanism would bring in a smooth symmetry of adjustments across countries and avoid global imbalances.

Keynes’ proposal was ultimately rejected; instead the US representative at Bretton Woods, economist Harry Dexter White, won out. The dollar was made the global reserve currency, at that time set at the fixed exchange rate of $35 per ounce of gold.

However, the drive in the 21st century by BRICS and much of the Global South to de-dollarize has led to a resurgence of interest in proposals like those made by Keynes.

The Russian BRICS chairmanship report did not explicitly call for the creation of such an international currency, but it did express interest in the concept.

The closest thing that exists, the document noted, is the Special Drawing Rights (SDR) issued by the IMF.

As an “alternative reserve asset and even the new global currency”, the SDR does indeed have potential, the report argued, but its use “remains limited”.

“Created as a supplementary international reserve asset, the SDR could have a bigger role to play”, the authors wrote, insisting that “efforts must be made regarding the utilization of SDRs in the real economy”.

They added, “With features and potential to act as a super-sovereign reserve currency, the SDR might be a solution to the long-standing Triffin Dilemma. That is the issuing countries of reserve currencies cannot maintain the value of the reserve currencies while providing liquidity to the world”.

Nevertheless, the SDR has a problem. Its value is based on a basket of five major currencies: the US dollar, euro, British pound, Japanese yen, and Chinese renminbi. Therefore, even if a sovereign country’s reserves in SDRs could not be frozen or seized, like the West has done to adversaries holding Treasury securities, taking loans denominated in SDR still poses an exchange-rate risk.

When the US Federal Reserve and European Central Bank rapidly raise interest rates, like they did in 2022 and 2023, this could lead to significant downward pressure on the currencies of developing economies, unless their central banks also raise interest rates, which could cause a recession and make it more difficult to pay off SDR-denominated debt.

As the Russian BRICS chairmanship report pointed out, “due to the interest-bearing nature of the SDRs (when drawn), the cost associated with borrowing in SDR is impacted by the currently high-interest environment of the countries that make up the basket of currencies comprising the SDR, which means further limitation to the practical use of SDR”.

Despite this problem, the authors argued that an international unit of account like the SDR could in other ways relieve exogenous pressure on the currencies of developing economies:

The SDR can help to eliminate the inherent risks of credit based sovereign currency and make it possible to manage global liquidity. And when a country’s currency is no longer used as the yardstick for global trade and as the benchmark for other currencies, the exchange rate policy of the country would be far more effective in adjusting economic imbalances. This will significantly reduce the risks of a future crisis and enhance crisis management capability.

The report indicated that it is not just Moscow that supports an increased role for the SDR, but also Beijing.

“China has begun reporting international reserves, balance of payments, and international investment position data in SDRs and renminbi. It has also issued SDR-denominated bonds”, the document noted. “However, market participants (as opposed to sovereign) have not started using the SDRs as a unit of account, and market infrastructure for the SDRs remains elusive”.

In short, the Russian BRICS chairmanship proposal expressed cautious support of the SDR and called to “promote the use of the SDR in international trade, commodity pricing, cross-border investment, and book-keeping”; to “create more financial assets denominated in the SDR to serve as an investment vehicle”; and to “reassess and strengthen the role of SDRs as international reserve asset, provided that measures aimed at increasing their utilization in the real economy and means of its exchange are successful”.

However, the fact that the SDRs are administered by the IMF means that they are unlikely to be a serious alternative, unless the IMF itself is fundamentally transformed.

De-dollarization of investment and reserves

In discussion of de-dollarization, it is important to distinguish de-dollarization of cross-border payments on one hand, and de-dollarization of savings and investment on the other.

In the international financial system, trade in goods is only a small percentage of total transactions; the vast majority involve capital flows into and out of bonds, stocks, and the foreign exchange market, along with hundreds of trillions of dollars of outstanding derivatives (financial bets) – a staggering $715 trillion as of June 2023.

In contrast, total global merchandise trade in 2023 was $23.8 trillion according to the World Trade Organization. UNCTAD calculated that world trade in goods in 2022 was roughly $25 trillion, and global trade in services was $6.5 trillion.

In other words, there is an order of magnitude between world trade and global financial transactions. Given this enormous disparity it is easier to de-dollarize international trade in goods than it is to de-dollarize savings and investment.

That said, the Russian BRICS chairmanship report proposes ideas of how to do both.

In addition to advocating the establishment of a de-centralized BRICS Clear platform, the document called for the “development of an investment hub on the continent of a platform member country”, with “new forms of debt issuance in place of the euro-denominated bonds – potentially denominated in national currencies of the participating countries”.

BRICS should create “an alternative to ANNA (Association of National Numbering Agencies)” that “will allow assigning and maintaining international ISIN, CFI and FISN codes for financial instruments denominated in the national currencies of the BRICS member states”, the authors wrote.

To encourage BRICS members to de-dollarize their reserves, they must make “other countries’ currencies (or a basket of such currencies) more attractive as a store of value”, the report stressed. This can be done by establishing liquidity-provision mechanisms and promoting the “proliferation of fixed income instruments denominated in local currencies to serve as an investment vehicle”.

The Russian BRICS chairmanship similarly proposed the creation of a BRICS Digital Investment Asset (DIA), which it said “will be backed by assets committed by the BRICS constituents”.

Given exchange rate risks in many emerging markets and developing economies, however, in addition to the massive momentum that incentivizes central banks and other investors to hold assets denominated in dominance currencies, the process of de-dollarizing reserves and other savings will be slow and difficult.

For decades, US Treasury securities have been the go-to global reserve asset. The question of what assets should be used to replace them is not easy to solve.

In the short term, the central banks of BRICS members have been investing heavily in gold, and its price is expected to continue to rise significantly.

The report emphasized, however, that the global economy has changed a lot in recent decades, while the international monetary and financial system has not caught up.

As of 2023, emerging markets made up 50.1% of global GDP and 66% of global GDP growth over the past 10 years (when measured at purchasing power parity, PPP).

The five original BRICS members comprised 32% of world GDP (PPP) in 2024. This is larger than the global GDP share of the G7.

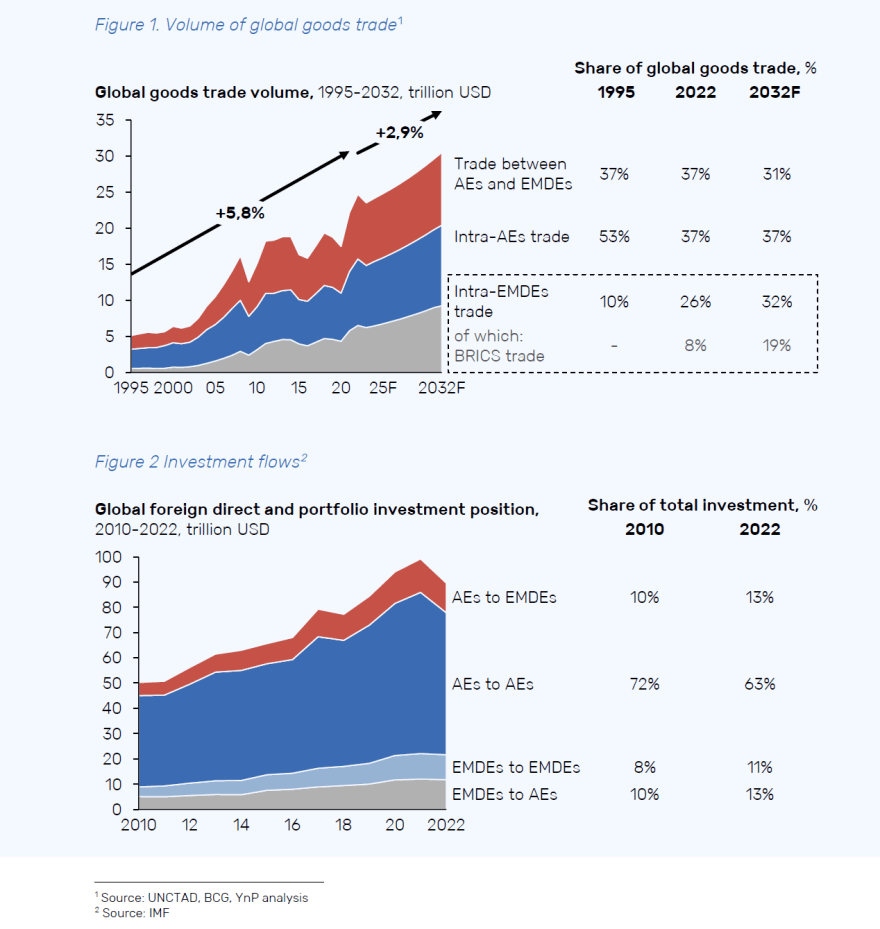

These changes are in part reflected in the shift in international trade flows. In 1995, just 10% of global goods trade consisted of trade among emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs); as of 2022, that figure had increased to 26%; and the report estimated it will reach 32% by 2032.

However, the significant changes in the global economy are not evident in international investment flows, which still disproportionately benefit rich countries.

As of 2022, just 11% of global investment flows from EMDEs to other EMDEs, and this figure has barely increased from 8% in 2010. The vast majority of global investment still flows from advanced economies to other advanced economies: 63% in 2022. This was slightly down from 72% in 2010, but the decline is small when one considers that EMDEs made up a staggering 66% of global growth in that same time period.

What this shows is that EMDEs have not significantly benefited from foreign investment, even though these are the fasting growing economies on Earth.

As the Russian BRICS chairmanship report put it, the “profits generated from growing trade are invested abroad into more liquid and accessible markets rather than benefiting domestic economies”.

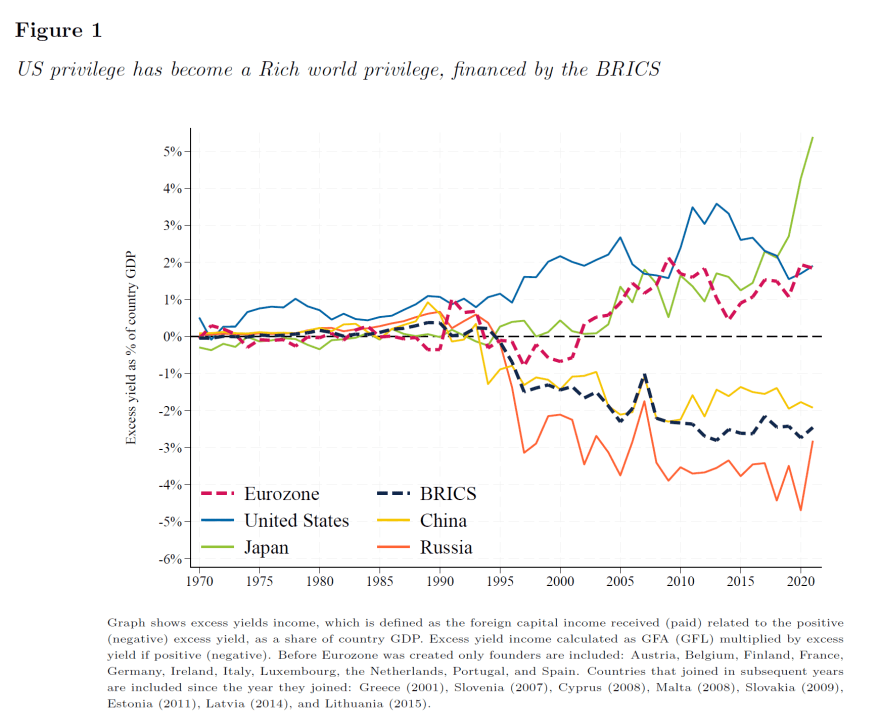

Economists at the World Inequality Lab, Gastón Nievas and Alice Sodano, came to a similar conclusion in a research paper published in April 2024. They wrote (emphasis added):

We find that the excess yield – i.e. the gap between returns on foreign assets and returns on foreign liabilities – has increased significantly for the top 20% richest countries (population weighted) since 2000. In effect, the exorbitant privilege of the US that was observed in previous decades has grown in size and scope and has become a rich world privilege.

The richest countries have become the bankers of the world, attracting excess savings by providing low-yield safe assets and investing these inflows in more profitable ventures. Such a privilege is translated in net income transfers from the poorest to the richest equivalent to 1% of the GDP of top 20% countries (and 2% of GDP for top 10% countries), alleviating the current account balance of the latter while deteriorating that of the bottom 80% by about 2- 3% of their GDP.

We show that rich countries accumulate positive capital gains, which improves their international investment position (IIP), and invest in relative less risky assets with respect to the world, refuting prior beliefs of them earning a return premia to compensate for potential loses and risk undertaken.

Our results seem to be explained by the fact that richer countries are issuers of international reserve currencies and are able to access cheaper financing (both for the public and private sector).

They summarized their findings in one sentence: “US privilege has become a Rich world privilege, financed by the BRICS”.

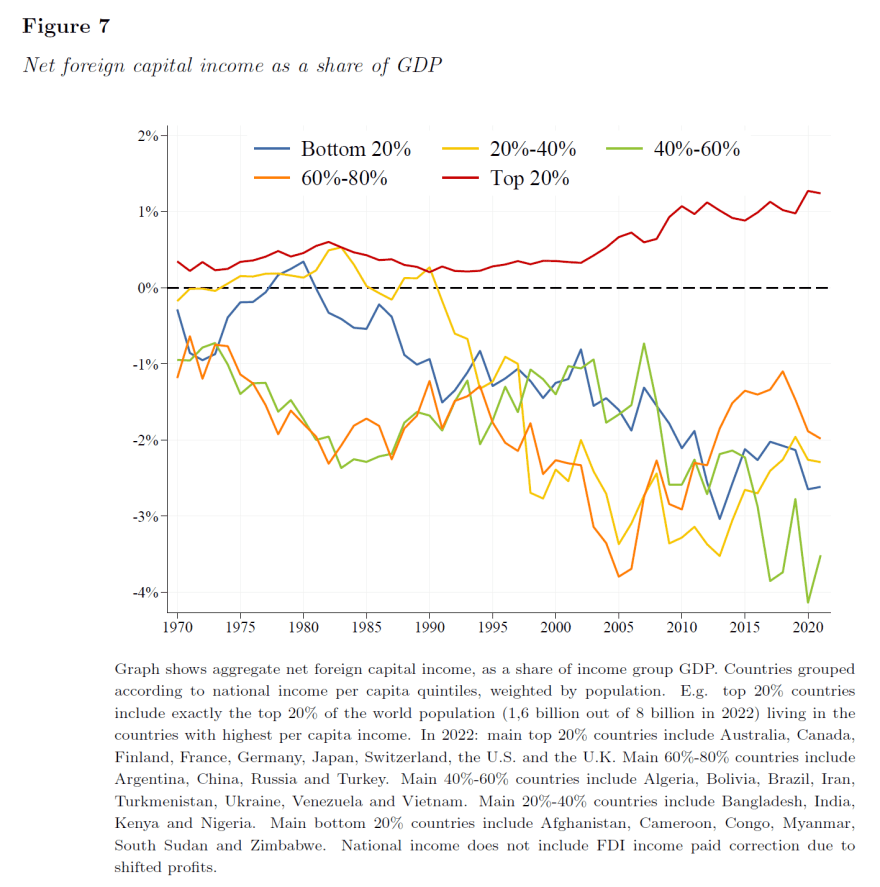

This drain of wealth from Global South to North is even clearer when the countries are separated into national income per capita quintiles.

Rich countries in the top 20% quintile receive more than 1% of GDP worth of net foreign capital income, whereas 2-3% of GDP is drained out of the rest of the world.

This drain of wealth has gotten worse since the rise of neoliberalism in the 1970s, and especially since the waves of financialization and deregulation in the 1990s.

The World Inequality Lab economists, Nievas and Sodano, explained:

In effect, the central position of rich countries in the international monetary and financial system allows them to function as intermediaries, akin to bankers of the world. This role further reinforces their privilege, as they leverage their advantageous position to attract excess savings and channel it towards productive investments. This cycle perpetuates their dominance and strengthens their position as key players in the global economic landscape.

They concluded their research paper writing (emphasis added):

We have argued that the rich privilege comes from an institutional design, contrary to the belief of being a market outcome, and that it entails huge burdens for poor countries. The bottom 80% are forced to transfer around 2-3% of their GDP each year, amounts that could be spent in developmental policies at home.

Efforts must be directed towards redesigning the current monetary and financial system to promote a more egalitarian regime. While the system has contributed to globalization, trade, financialization, and economic growth, it has failed to address complex challenges such as climate change, technological innovation, rising inequality, long-term demographic changes, and escalating geopolitical conflicts in a multiplex world.

The initial promise made after World War II to establish a neutral international monetary and financial system remains unfulfilled. We argue that the United States has not earned its privileged position of the US dollar, but this privilege was inherited from a time when it was imposed during the early years of the Bretton Woods system. Although it is true that dollar reserves have been accumulated voluntarily by the rest of the world, the initial role of the dollar as a stable global currency has allowed the US to become the currency hegemon and to capture an exorbitant privilege while tilting the international balance of power in its favor. So far, its hegemony has only been partially contested by other -rich- currency provider countries.

While the Russian BRICS chairmanship proposal will not solve all of these structural problems, it is a step in the right direction.

The BRICS report itself concluded with a cautious tone. “The extent to which the current system has deviated from the proposed model means that the change will take time and will require collective effort across the countries”, the authors wrote, emphasizing that “practical implementation of the aforementioned initiatives will take a phased approach”.

However, the document added, “The important thing is that the process has already begun – alternative payment systems and financial messaging mechanisms are already here, the use of national currencies for bilateral settlement is growing and new ways of transacting, including digital assets, are emerging”.

The BRICS proposal to transform the international monetary and financial system is far from a panacea, but it could be a step toward rectifying some of these structural inequalities.

In this sense, the BRICS plan could be seen in the same vein as the call for a New International Economic Order (NIEO).

The G77 has reiterated its demand for a NIEO virtually every year since it was first issued in 1974.

The G77+China held a summit in Cuba in January 2024, in which participants denounced “the major challenges generated by the current unfair international economic order for developing countries”. That same month, Cuba, as president of the G77, hosted the Havana Congress on the New International Economic Order.

All BRICS members except for Russia are part of the G77, and Moscow has long supported the call for the NIEO.

It is therefore deeply appropriate and symbolic that BRICS is discussing plans to transform the international monetary and financial system on the 50th anniversary of the NIEO.